Lily Kwok

郭莉莉

Born: Diego Martin, Trinidad and Tobago

Raised: Glencoe, Trinidad and Tobago

Glencoe, Trinidad and Tobago

Lily Kwok is an excellent writer from Trinidad and Tobago, an island east of Venezuela.

I came upon her through her excellent writing about her Chinese identity, so I emailed her. Online dating has honed my skills of cold messaging and expecting nothing.

In my opinion, her magnum opus has to be To Look Like Me, To Sound Like Me.

History on this Chinese migration story

Lily read my article where I asked Wanrong why her family migrated to Mexico, rather than directly to the U.S. or Canada. To Lily, it simply came down to better opportunities regardless of location.

“It’s called the New World. You think that things can happen here. Things can change here. For some people it’s not easy to go to the US, Canada first. You end up in Mexico and Peru and Trinidad, Jamaica and sometimes that’s a pathway for your children to actually get to the US once they go to school,” she said.

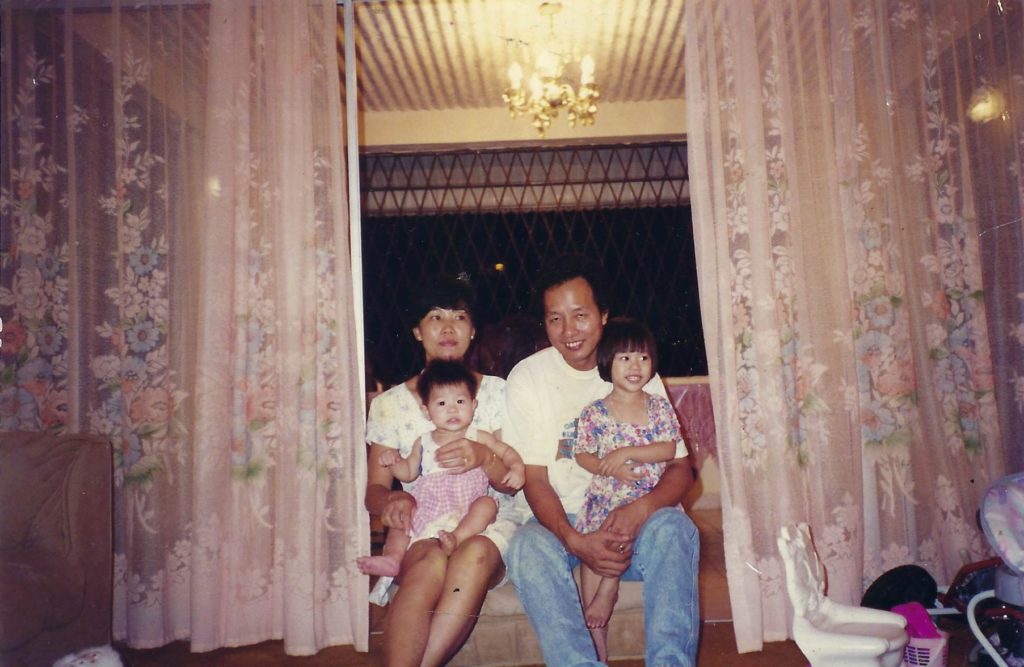

The history of her family’s migration was a bit hazy, but Lily said that the first person to arrive in Trinidad was her paternal great-uncle, who brought over her uncle. They owned businesses like supermarkets, and that was when her uncle invited her father to come to Trinidad in the late ’80s to work in the supermarket.

Her father grew up in Zhongshan in Guangdong province and lived in Hong Kong and worked in restaurants. Lily described his youth as “pretty rural, pretty poor.” Her uncle invited his father to visit Trinidad and her father decided he wanted to stay.

In Lily’s estimation, her parents are far better off in Trinidad than they would have been if they stayed in East Asia.

Same same

For a long time in Southeast Asia, you’ll see shirts with the slogan “same same, but different.” So let’s tackle the “same same” part first.

In some ways, I saw many similarities between Lily’s life in Trinidad and mine. Trinidad and Singapore were both British colonies until the big post-war decolonization phase in the 1960s. Trinidad and Tobago got their independence in 1962 while Singapore got its independence from the UK in 1963, then full independence (from Malaysia) in 1965.

It seems rather farfetched that Lily, from the West Indies, can have so many similarities to me, who grew up close to the former Dutch East Indies. For one, we were both tropical people and we both spoke English as our first language. Sort of.

Creole and Singlish as real first language

Lily mentioned that she had a “Creole-lashing tongue” and that “we, island people, inherit Creole long before we ever touch English.”

Funny, I am an island person who also had a Singlish-lashing tongue, lah. Then hor, only later then I learn English one.

Communication among Singaporeans can be very centred around speaking Singlish. It runs deep as the lowest common denominator of peoples who might speak English, Chinese, Malay or Tamil.

I suppose learning a language by mimicking others is easier than learning a language with its many rules and structures, which is probably why we’re seeing so much gross abuse of apostrophe’s these day’s.

“When I talk to non-Trinidadians, even you, I accommodate. So I try to speak as clearly as possible, so this is not necessarily my full Trinidadian accent,” she told me.

I imagine being able to speak standard English and use apostrophes properly comes with education and practice. And that on the streets of Trinidad and Tobago, speaking Creole would be the lingua franca that cuts across all educational attainment.

Divali and Deepavali

Lily mentioned how Trinidad was a small place with a small population and that meant that people of different backgrounds intermingled.

In this, I saw how British colonialism spread its patterns throughout the world. Trinidad and Tobago is a third African and a third South Asian. Singapore has a small population of Indians too, a bit less than 10 per cent.

“Everyone celebrates Divali, everyone celebrates Eid together, everyone does all the holidays and a lot of mixing happens, so we have a lot of mixed race people,” she said.

So, Trinidadians have Divali and Eid, Singaporeans have Deepavali and Hari Raya Puasa.

Small country problems

I completely understood what Lily said when people feel flabbergasted when she says she’s from Trinidad.

She said, “My appearance combined with my voice conjured cognitive dissonance in anyone who was not familiar with the demographics of Trinidad and Tobago (which, believe it or not, is most people).”

Oh boy, let me tell you about the question that is, “What do people speak in Singapore?”

When I tell them that we speak English, some folks would erupt like a Coke that’s been shaken up vigorously. Just as I would erupt internally when people misplace Singapore as a place in China.

Double standards? Lily writes,

“For instance, we see it in admission processes, where the idea that some Englishes are more valid than others is applied. Despite English being the official language of instruction of my Bachelor’s degree, I must take a standardized test to prove myself. Not only must I take this test (and do well), I must spend a significant amount of money to register. A similar paradigm exists in the professional sphere of education. When hiring an English as a Second/Foreign Language teacher, recruiters often prefer candidates who speak a variant of English from the U.S., U.K, Canada, Australia, or sometimes, South Africa. Speaking English as a Jamaican or Singaporean does not hold the privilege of consideration.”

To Look Like Me, To Sound Like Me – Lily Kwok

I don’t blame people who are ignorant about Singapore, though. If you asked me about Liechtenstein, Dominica or Papua New Guinea, I’ll have no damn clue.

But different

A lot of what I have written between the similarities of a Trini person and a Singaporean person centres on our similarities being from a non-white British colony.

Beyond that lies the bifurcation between the two of us. Singapore is over 70 per cent Chinese while Trinidad and Tobago has a population of 1.39 million with about 4,000 being Chinese, which is 0.29 per cent. About 250 times less in proportion. These figures come from Wikipedia, which in turn comes from Trinidad’s 2011 census.

Being Chinese in Trinidad and Tobago

Lily sees herself as Trini first and then Chinese, but when it comes to whether Trini society accepts her as their own, her answer was, “it’s a weird mix of integration and exclusion.”

I felt rather surprised that Lily felt less noticeable when she went through graduate school in small-town Mansfield, Conn., located equidistant from the prestigious MIT to the northeast and Yale to the southwest.

“I mentioned that in Trinidad I am very visible. People just notice you. They just see you and they’re like, ‘OK a Chinese person.’ When in the U.S., nobody cares. Nobody double takes or notices me, really,” she said.

In Trinidad, Lily recounts growing up with a mix of Chinese, Western and Caribbean values.

Writing Eric Yuan’s article made me realize that there were certain parents who would forcibly speak the local language to their children even though they weren’t very good at it.

It came down to the parents’ desire for their children to integrate into society.

“I consider Cantonese my heritage language in that I’m not fully fluent in it,” she said. “My dad really only tried to speak in English even though his English wasn’t very good.”

There weren’t any Chinese schools in Trinidad and the only person who Lily would speak Cantonese with is her mother.

Her parents burned incense and practised Buddhism, but both Lily and her sister were baptized.

“They never talked about Catholic doctrine with us but they definitely tried to get us assimilated and this is how they thought that would happen. English, Catholicism,” she said.

Yet at the same time, I got a sense Lily doesn’t feel that Trini society accepts her fully. In her article, she mentions how she’s the token Chinese person who gets labels like “first Asian friend” all the way to being a trophy as the “first Chinese girl I ever [had carnal relations with].”

“I do feel my Trinidadianess denied a lot,” she said. “They don’t think I’m from here. They always ask where I am from. They assume I migrated here even though I was born here. There are a lot of stereotypes. People kind of ‘other’ me– assume I’m foreign,” she said.

Is Lily’s real name even “Lily?” Apparently, all Chinese women in Trinidad automatically get the name “Mary.”

What if Lily were born in China?

At the same time, Lily recognizes that her life would have been significantly different if she grew up in China. She points to her cousin, who’s about her age, and says that she is married and has children, while she has neither. She chuckled after saying this.

I replied that this could be the narrower path people in East Asia might be following whereas in the West, marriage and kids might not be a significant marker of a person’s progress. Perhaps this is a conversation between collectivism and individualism.

However, on the topic of Chinese values, Lily does say she has adopted her parents’ work ethic, and just like every other person I have interviewed, Lily has a masters degree. In fact, Lily was enrolled in a PhD but dropped out.

Did I also mention she went to law school? She switched one year in and studied English Literature instead, graduating as the valedictorian of her faculty.

Navigating race relations as a Chinese woman in Trinidad and Tobago

One of the most distinct patterns in former British colonies is racial conflict.

Think about northern Indians and southern Indians. Think about Myanmar. Think about Uganda and Guyana. Heck, Singapore also had racial riots in the ’60s.

Lily said she has sensed a lot of friction between Indian Trinidadians and African Trinidadians.

“Last year, we had general elections and I don’t know if it’s social media, but it felt even more racist than usual,” she said.

Lily described how political parties were split down racial lines. So how does a Chinese person identify with this system? To Lily, it could come down to class.

“If you are a wealthier Chinese person, you don’t speak Chinese at all because your parents and grandparents have been in Trinidad, you might socialize more with wealthier people who might be white or a light-skinned Indian. I have seen that where upper-class Chinese people only hang out with Indian people,” she said.

In a Quora post that lists the richest people in Trinidad, it seems that the top three richest people are Indian. There is one Chinese name in there, which makes Chinese people significantly overrepresented on that list (10 per cent on the top 10 list, 0.29 per cent in population).

“But I guess everyone else’s intermingling really depends on your personal values and where you grew up.”

Lily added that because she grew up around a lot of Black Trinidadians, her friends are also naturally made up of them.

“There is privilege in being lighter skin”

Meghan Markle’s recent revelation that someone in the British royalty had “concerns and conversations as to how dark [her son’s] skin might be when he’s born,” shocked the world, but Lily relayed to me that Trinidadian parents could very well have had this conversation.

When she was very young, a boy held a white colour pencil against her arm and said, “Yuh skin like dis colour pencil!”

Certainly, being Chinese in Trinidad and Tobago doesn’t make Lily the fairest of them all. There’s a small population of Europeans, Syrians and Lebanese people, who have a higher probability of being wealthy.

Lily elucidated to me that being Chinese in Trinidad means being a “model citizen” and that police would generally not suspect Chinese people of committing crimes. There’s also a perception among people that Chinese people are rich, as the most visible ones are businesspeople who run supermarkets and restaurants.

In her personal experience, Lily realized her privilege in various areas.

I asked her if she thought Trinidadians saw Chinese people as more attractive due to our skin being lighter in a Trinidadian context. She told me that society perceives lighter skin as more beautiful, but that is also tied up with the exoticism and fetishization of Asian women in the West. So, I hesitate to conclude anything here.

But more importantly, she observed certain Indian-Trinidadian families ostracizing their children because they dated someone who was Black. Some would keep those relationships a secret for fear of reprisals. Yet, this wasn’t the case with an ex of hers.

“I once dated a person of Indian descent as a teenager. His parents adored me, in part because I was Chinese,” she said. “My ex told me that when he was previously dating a Black girl before me, his mother was upset and was concerned that she would not be able to ‘comb the hair’ of her future grandchildren.”

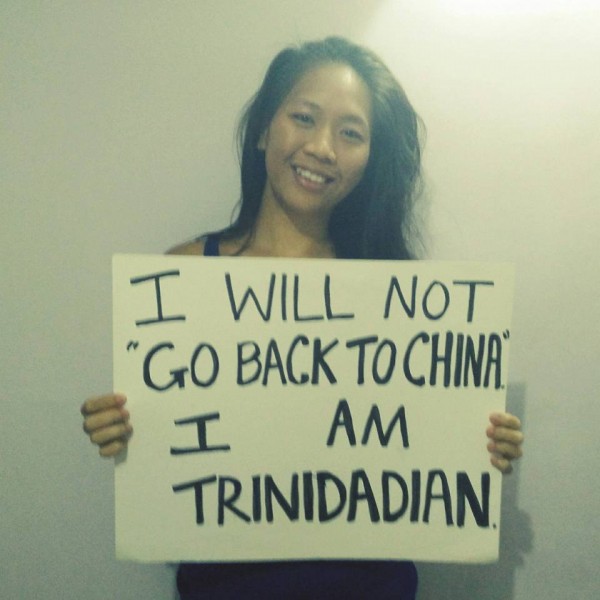

Lily, an activist of #StopAsianHate

Lily led a campaign in 2015 condemning the health minister’s comment about Chinese restaurants. Again, just like in northern Mexico, it’s about dogs.

The crux of the issue was that a video of unknown provenance surfaced showing two men skinning a dog. A health minister went on a newspaper and made a few suggestions, including,

“We normally have stray dogs and one wonders if the Chinese restaurants, those which have sprung up all over the place have been serving dog meat and something else,” he said.

I’d encourage you to go read the article yourself and make your own conclusions. I didn’t really pursue this topic much further with Lily because she has already given an interview with another blogger.

But in sum, Lily described the experience as, “quite a painful and anxiety-inducing experience for me.”

And therein sparked her social media campaign with her sharing the above image. I couldn’t find any actual social media posts because this incident is six years old, but another news site has documented some responses.

Most of us Chinese would stay silent. In this era of #StopAsianHate, Lily inspires me to take action.

Leave a Reply