This article was written based on the podcast Esto Pasó Posta which had an episode talking about being Chinese in Argentina, entitled “Ser chinos en Argentina” which they released on Aug. 25, 2021.

Early history of Chinese immigrants in Argentina

In the last few decades, there have been waves of migrations from China to different parts of the world.

Many of them, from a poor background, set out in hopes of finding opportunities of a better life for their families, ended up in South America.

Most Chinese immigrants living in Argentina did not arrive working for Chinese multinationals but by their own means. In the ‘90s there was a wave of migration from China, mainly from the province of Fujian, which focused on one type of business: supermarkets

Currently, it is estimated that there are more than 200,000 people of Chinese origin in Argentina.

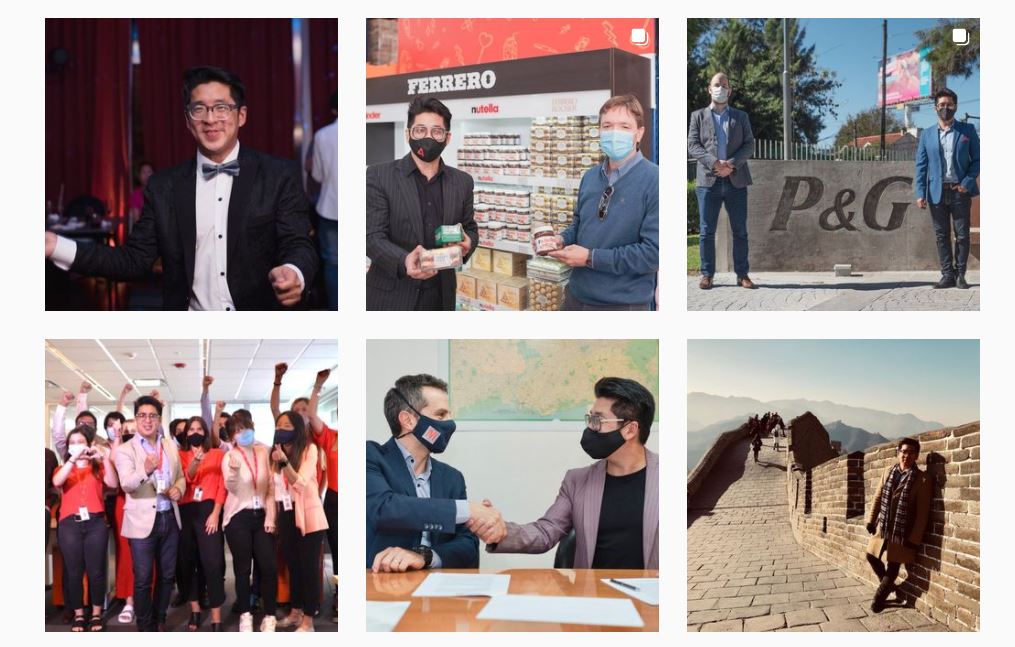

Here are two stories of Chinese people living in Argentina.

Carlos Lin: an Argentina Chinese story born among political conflicts

Our first story is about Carlos Lin. He is a journalist, radio broadcaster, television host, and COO of Aliwan Argentina.

He begins his story by saying that the story of a Chinese person is always the story of a lineage. This brings into meaning the importance of family and community in Chinese culture, where the story and achievements of an individual are never solely about the individual per se, but it is also the story of the ones that came before.

Moreover, throughout his narration, we will see that historical events not only have an impact on the main characters involved in them but also on the families that are affected by them.

What caused this Chinese family to immigrate to Argentina?

Carlos starts with the story of his grandfather, a sea merchant from Taiwan, who meets his grandmother in Nanjing, the previous capital of China. They get married and in 1949 their first son, Carlos’ older uncle, is born and the family moves to Taiwan. In 1953 Carlos’ father was born, who later met his mother at school.

In 1975, conflicts between Taiwan and mainland China led to an economic crisis, so Carlos’s grandfather decided to move the family to South America with hope for new opportunities for a better life.

They end up 18,000 kilometers away from home and amidst the Falklands/Malvinas War. In 1980, Carlos Lin was born in Santa Cruz de la Sierra, Bolivia, the place where the family first arrived, and then in 1982 the family moved to Buenos Aires, capital of Argentina.

When they arrived in Buenos Aires, the family started a faux jewelry shop. Meanwhile, Carlos and his older brother Pablo frequently played soccer in the streets with the other children of the neighborhood.

Carlos says he and his brother integrated easily into Argentinian society, compared to other Chinese peers like his cousins, because of their talent for playing soccer.

Carlos mentions he was referred to as “el más porteño de los chinos“, which translated into “the most ‘porteño’ of the Chinese“, with “porteño” referring to the people of Buenos Aires.

He credits this to his expertise in speaking perfect Spanish with no difficulty in rolling his R’s.

One day, Carlos saw a person walking the streets with a group of people following him closely and trying to take his picture.

Carlos asked who that person was and it turned out to be Roberto “el polaco” (“the Polish”) Goyeneche, a famous tango singer.

Carlos explains this was the first reference to an icon of “porteñidad,” or Buenos Aires’ cultural identity.

So Carlos says after this event he began building this identity consisting of soccer, “barrio” (ghetto), and tango.

Later in the 1990s, a reform in the importation policies made the importation of items from China and Taiwan very difficult. Because of this, the Lin family was forced to change businesses, so they sold their house and opened a supermarket. Carlos says people don’t see the ugly side of running a Chinese supermarket.

“[There is] lots of sacrifice, lots of hard work, and lots of deprivations,” he says. Many times these Chinese immigrants, mostly from poor families, have to leave their home country in order to provide for their children or parents, or in some cases even both, who stayed back in China.

Carlos says currently there are more than 220,000 Chinese people in Argentina. The differences between both cultures create a barrier for the Chinese immigrants to adapt well into Argentinian society. Argentinians and other Latin American cultures are generally warm and usually express their affection with physical contact, something that is rare in Chinese culture which generally establishes a certain distance. These differences create a gap between the Chinese and Argentinians, which also creates misunderstandings, and in turn, they are not easily accepted by the locals.

Additionally, a Chinese immigrant who is having a hard time adapting into society and struggling with learning a new language, might have in their mind many other needs they have to meet, like providing for their families as mentioned before, before trying to fit into society and have a good time.

Chinese hierarchical interactions poses intercultural challenge in Argentina

The next story is about Alejandra Conconi, she is the Executive Director of the China-Argentina Chamber of Commerce. She has a Bachelor in Oriental Studies and specializes in the workplace relationship between Chinese and Argentinians.

She has lived and worked in China and works as an intercultural expert for Chinese companies located in Argentina.

Alejandra says that the most common misunderstanding that happens between Chinese and Argentinians is the short circuit in communication, like wrong interpretations and stereotyping.

She explains that when a Chinese superior gives a task to an Argentinian employee and it is completed, the Chinese superior does not give response or feedback.

The absence of feedback is perceived by the Argentinian employees as a gap, giving a chance for misunderstanding. Yet this is not the case for the Chinese because they are used to working with a certain distance in hierarchical power.

As mentioned above, one issue that Chinese immigrants have to face even before they step into Argentina is the language barrier. They are forced to quickly learn a survival level of Spanish for the workplace and for communicating in their daily lives. Some people learn an excellent level of Spanish in the span of ten years, and some others can’t speak in the same amount of time.

The difficulties of learning Spanish impact not only the lives of the adult immigrants, but also that of their children. Many times the young children of Chinese immigrants are forced to become adults at an early age to help their parents because the parents can’t learn the language fast enough. The children may find themselves having to translate for the doctor, migration or tax agent, situations that a child is not ready to handle or take responsibility for.

“Going to the Chinese” means going to the supermarket

The last story is about Lily Ohayo, she is a lawyer, professor, and influencer on subjects that include antiracism and Chinese culture. Her family is from Shanghai and she was born in Argentina.

She expresses that, growing up, she had to perform the “outside” culture, Argentinian, and the “inside at home” culture, Chinese. She describes this as sensing a duality in her body.

Lily also speaks about the obligations of the first-born child in Chinese culture, who has to assume the role of a third adult, assisting the father and mother.

Many times the eldest child of Chinese immigrant families has to assume responsibilities that their Argentinian peers or classmates don’t have, and find themselves dealing with adult issues as well as children’s issues at the same time.

Lily expresses that she personally does not consider this responsibility as a burden and, on the contrary, she chooses to gladly assume said responsibility and does it with pleasure.

In her social media, Lily speaks about reflecting, introspecting, becoming uncomfortable, and challenging the established paradigms about race and culture. She describes it as the information she would have liked to have when she was younger, when she did not know what racism was.

She also talks about the racism she has faced from a young age, about how people would judge and assume everything about her life because of her face and appearance, making assumptions about her abilities (assuming she can’t speak Spanish), her occupation (assuming her family has a Chinese supermarket), and judging her without knowing her or even being interested in corroborating such assumptions.

In addition to facing racism for being Chinese, Lily has also faced sexism for being a woman. She recounts an event in which a man approached her and called her “chinita, china“, meaning “Chinese girl.”

The Chinese immigrants never completely adapt because they feel unwanted and unwelcome because of these microaggressions. In her Instagram, Lily further explains about an event (but it is not clear if they are the same or a separate one) in which somebody yelled at her “¡Te chupo toda la concha, china!,” which translates into something like “I’ll suck your pussy, China girl.” Her immediate response was to clarify she is Argentinian, with the only thing in her mind being refusing to stay quiet. And the man responds, “I’ll lick it anyway.” And so it clicks: if it ain’t for being Chinese, then for being female.

Lily’s Instagram also touches on the subject of Chinese supermarkets in her social media. It is estimated there are more than 8,000 supermarkets under Chinese ownership in Argentina.

Additionally, the expression “ir al chino” or “going to the Chinese” is Argentinian slang that refers to going specifically to a Chinese supermarket.

“There’s no other business that’s being called on by the characteristics of the owners, only it’s towards the ones owned by Asians”, Lily writes in an Instagram post. “With this logic, if a business was owned by a visually impaired person, would you ever hear ‘I’m going to the blind’?”

“What I would have liked to know [when I was younger] is that they [Argentinians] don’t really hate the Chinese. Instead, they have a highly self-referential way of thinking. And that in some way, it’s not that they hate us, but it’s simply that they are constantly searching to confirm their own ideas and beliefs,” Lily explains.

“The Chinese immigrants’ process of adaptation is never-ending”, Lily says. “Argentina is a very racist country, yet Chinese people love their community and enjoy living in Argentina.”However, the prospect of one day going back to China still remains. Not because it is a better country, but because she will never be called “chino” or “chinita” on the streets.

Leave a Reply